Using Census Data in Historical Research

Labor and social historians have long relied on historical census data, which remains some of the richest data on the lives of everyday people. We also know that this data source, like any other source produced by humans at a particular moment in time, reflects the assumptions and concerns of its authors. Thus, we should approach the census like any other historical source. This essay provides some historical context for understanding census data, how it was digitized into IPUMS microdata samples, and how I use this data in The Education Trap.

The Census as a Historical Document

Beginning in 1790, about 650 US marshals and their assistants were charged with travelling across the original 13 states plus the districts of Kentucky, Maine, Vermont and the Southwest Territory to collect demographic information about each household. The first census only included six inquiries: the name of the head of household, the number of free white males over and under sixteen, the number of free white females, the number of other free persons, and the number of slaves. In subsequent decades, new inquiries were added or subtracted, reflecting the priorities of the time. For an excellent and comprehensive history of the U.S. census, see Margo Anderson’s The American Census: A Social History, first published in 1988 and now in its second edition; for the specific questions asked each decade, see the U.S. census publication, Measuring America: The Decennial Census from 1790-2000 (2002).

The data recorded in manuscript form was then prepared into aggregate statistics for publication (now available on the U.S. Census website). These published census statistics are still widely used for historical research, but present some limitations. The aggregate categories are often too large, or broken down in ways that don’t match a historian’s particular questions. In manuscript form, while individual-level census data presents the possibility of much more fine-grained analyses, it is more difficult to use and access to the manuscript returns themselves is restricted for 70 years after collected. Researchers have created their own small samples of individual-level data for specific projects, but collecting these samples is extremely laborious and time-consuming.

IPUMS microdata census samples

The Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS-USA), a project of the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota, has its origins in the 1960s, when the U.S. Census Bureau created the first .01% public use sample of anonymized, individual-level data from the 1960 census. Improvement in computer technology by the 1990s allowed for larger sample sizes to be digitized, and the internet allowed for broader dissemination and use of this data, which quickly became an indispensable tool for social scientists. These samples allowed for much more fine-grained analysis and flexibility in aggregating tailored categories.

Confidentiality restrictions limit access to the original manuscript censuses, but after 70 years, the IPUMS team was able to create much larger samples. Working in collaboration with the Church of the Latter-Day Saints, which digitized images of the original manuscript censuses in the website Ancestry.com, by 2017 IPUMS had created complete-count, 100% samples of each U.S. census from 1880 to 1940. These full-count datasets offer the most complete coverage of individual-level data and allow for extremely detailed analysis of small populations. IPUMS also offers linked census data for individuals between 1900 and 1940.

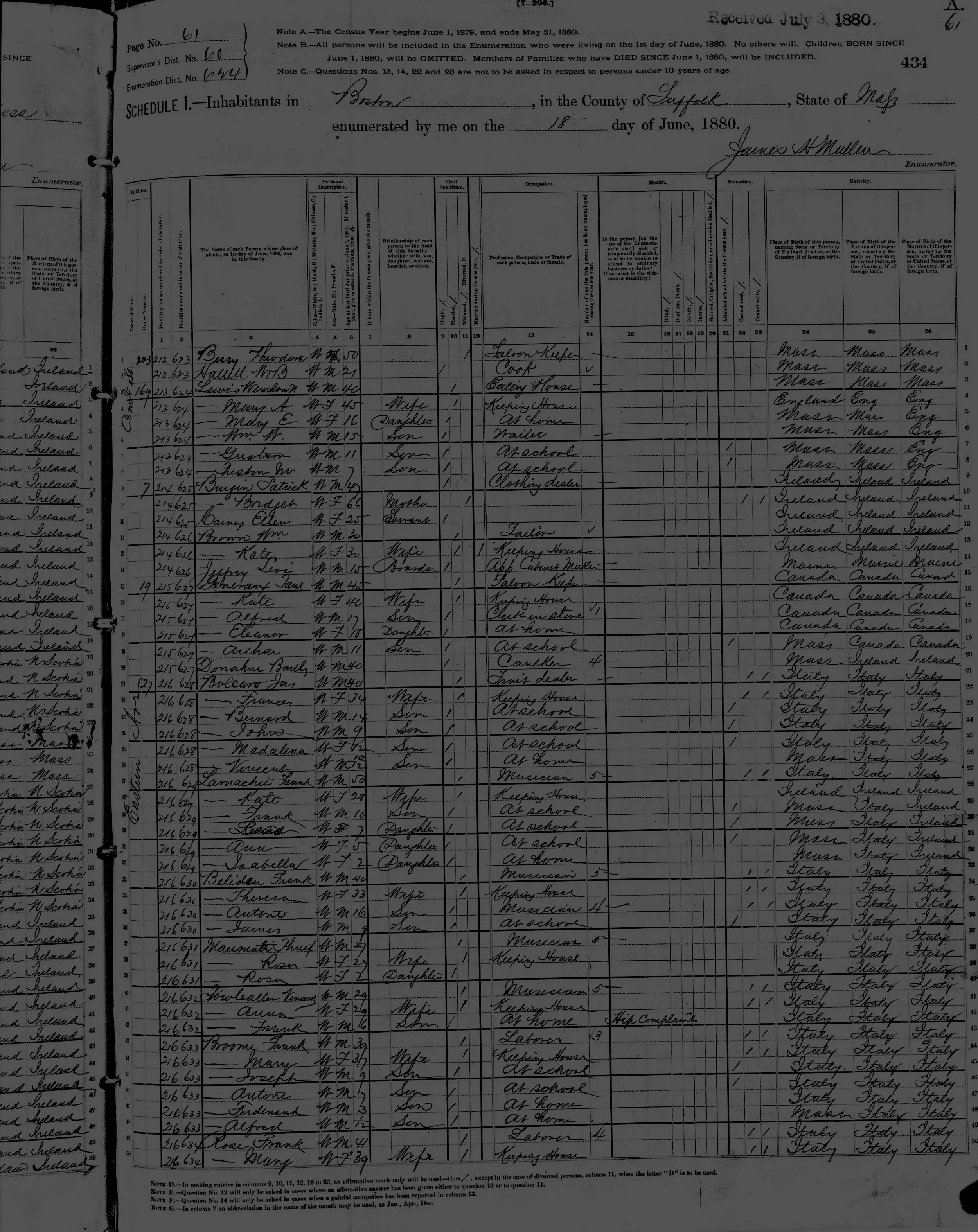

Ancestry.com digitized manuscript census

Another important tool for historical research is the manuscript census itself, available up to 1940, especially now that it has been digitized by Ancestry.com. This searchable database allows the researcher to search for a specific person and trace an individual through multiple censuses as well as in other digitized records (including marriage licenses and naturalization records). It also allows the researcher to examine specific neighborhoods or street addresses in the manuscript census to get a better sense of who lived in the neighborhood and household characteristics at a specific time.

How I use occupational data

One of the primary ways that The Education Trap uses census data is for insight into the working lives of Bostonians. Occupational data—collected in the U.S. census starting in 1850 for men over 15, by 1870 for men and women of any age—is one of the best resources. However, occupational data also poses a number of challenges and limitations. Margo Anderson’s The United States Census and Labor Force Change: A History of Occupation Statistics, 1870-1940, published in 1980, has been crucial to a generation of scholars who use census data in their own research. Anderson reveals the myriad of ways that the collection, classification, and interpretation of occupational statistics both reflected the concerns of census takers as well as their assumptions and prejudices. Anderson’s book was published at the height of a wave of quantitative social history research using census data and occupational statistics to explore social mobility, social inequality, and class formation. With the rise of new digital technologies that have made these statistics easier to use than ever before, historians confront similar questions about the limits of this data, and how can we use historical data responsibly and critically.

I use occupational data in The Education Trap in a variety of ways. First, I use it as the basis of a snapshot of overall workforce participation at a given time. The census takers recorded self-reported occupations, which offer an approximation of the bulk of paid work in the Boston economy, but notably does not account for all work. Unpaid care work or household labor, mostly performed by women, was not recorded as an occupation in the census. (The work of wives was often listed as a non-occupational response, “keeping house.”) Moreover, those who performed piece work in the home, or performed sexual or illicit labor, received wages that are not accounted for in the census occupational categories.

I used the IPUMS occ9150 variable for a basic measure of occupations. Occ1950 adopts the 1950 occupational classification scheme and reclassifies prior censuses according to that scheme to create a consistent and comparable set of occupations from one decade to the next, which was important for a study that spanned the period from 1880 to 1940. This reclassification was performed by the IPUMS team directly from the original manuscript census data, rather than from a prior occupational classification system, mitigating errors that might arise from reclassifying data a degree or more removed from the original source. For Chapter 1 that focuses on 1880, I also compared my occupational results to those tallied using the occ variable (based on the original occupational classification) as well as occstr (a string variable of the actual occupation as written in the census) for additional context. For example, the occ1950 scheme lumps all “managers, officials, and proprietors” together as one occupation. However, a street vendor or peddler belonged to a different class position (what I call a “world of work” in the book) than a wholesale merchant. Using the occ and occstr variables, I could more narrowly identify the type of proprietor and make a more informed historical estimate about what percentage of “managers, officials, and proprietors” who belonged to the economic elite versus the working class. The IPUMS 1880 sample also includes the variables namefrst and namelast—a string variable of the name of the individual listed in the census—which allowed me to look up a sample of individuals in key occupations in the manuscript census using Ancestry.com. I used these samples to provide additional context about the typical household characteristics for a specific occupation. For example, looking up a sample of tailors allowed me to see whether the majority had a domestic servant, if the home was a single family home or tenement in a larger building, whether children were working or in school, among other characteristics. This context helped me paint a more accurate portrait of each occupation and each world of work.

I used occupations to categorize individuals into 5 major sectors of work: 1) Professionals, 2) Managers and Owners, 3) Clerical and Sales Workers, 4) Craftworkers, 5) Operatives (in factories and of vehicles), 6) Personal Service Workers, and 7) Laborers. These categories roughly match the IPUMS occ1950 classification scheme. Classifying occupations into sectors, however, is a contested process, both historically and in contemporary social science research. Social scientists commonly use categories such as “blue collar” and “white collar,” or labels referencing skill level (unskilled, semi-skilled, skilled). However, the collar line was not a clear marker of status or wages in the late nineteenth century. The average sales clerk in 1880 made less income than a machinist, for instance. In addition, “skill” level is a socially constructed category that often incorporates gendered, racial, and ethnic assumptions into its definition.

In light of historical context, I made some adjustments to which occupations belonged in which sector. I made two changes to correct for the common downgrading of women’s occupations, based on gendered assumptions about skill. As discussed by Margo Anderson, highly-skilled crafts performed by women were often placed in a “semi-skilled” category, rather than with comparable trades performed by men. In the IPUMS occ1950 scheme, “dressmakers and seamstresses, except factory” and “milliners” are grouped with “operatives,” alongside other factory and vehicle operators that were typically paid lower wages. But women dressmakers and milliners, especially in the late nineteenth century, were what historian Wendy Gamber has called the “female aristocracy of labor” and occupied a different position than their counterparts in factories. Thus, I moved women in these occupations to the “craftworker” category to better reflect their position as a trade. “Boarding and lodging housekeepers,” predominantly women, were originally classified with low-wage service workers. However, boarding and lodging housekeepers were historically closer to that of a small proprietor than that of a domestic worker. Thus, I moved these women to the “small proprietor” category. A third change was made to differentiate between sellers of goods. “Hucksters and peddlers” were originally grouped with sales workers, but I moved them to the low-wage category to better reflect their status and lower pay than most salesmen or sales clerks.

Using occupational variables to trace changes in the economy over time introduces its own host of problems of comparability and classification. The entire economy was undergoing rapid transformation in this period, changing the nature of occupations themselves, which means that they are not perfectly comparable from year to year. As a rough approximation, however, these changes can illustrate important occupational trends: for example, the rapid decline of domestic work for women, and the rise of clerical and sales work. To supplement the limitations of a fixed occupational scheme, I also relied on qualitative sources to provide context on the changes in the nature of the occupations from 1880 to 1940.

How I use data about race and ethnicity

There are two basic types of information about race and ethnicity in the censuses between 1880 and 1940: race and birthplace. These indicators make for imperfect but valuable measures of race and ethnic background. In 1880 and 1900, options for “race” included “White,” “Black” or “Negro,” “Mulatto,” “[American] Indian,” “Chinese,” and “Japanese.” Census takers could also indicate “other” as a racial category in 1910. In 1930, census enumerators were instructed to use, in addition to the racial categories listed above, “Filipino,” “Hindu,” “Korean,” or “Mexican.” In 1940, enumerators were instructed to report “Mexicans” as “white,” and report all “mulatto,” “Black,” and those of “negro blood” simply as “Negro” in the census.

Throughout this period, birthplace, father’s birthplace and mother’s birthplace were recorded by the census enumerator. Using the birthplace (“bpl”)variable, it is possible to determine how many individuals in Boston were foreign-born immigrants. Using father and mother’s birthplace (“fbpl,” “mbpl,”) I also create a measure of ethnic background that goes back one generation. Because it is not possible to go back more than one generation, measurements of ethnic background are likely underestimates of those with a specific ethnic background. For example, the granddaughter of Irish immigrants (if born in Massachusetts with parents born in Massachusetts) would not be classified as “Irish” but with other individuals with Massachusetts parentage.

Because there were such high levels of immigration during the nineteenth century and turn of the century, the majority of Bostonians were first or second-generation immigrants between 1880 to 1920. However, due to immigration restriction in the 1920s, the number of immigrants greatly declined. The proportion of Bostonians classified as having “Massachusetts parentage” rose, and third-generation immigrants were no longer visible via census data. For that reason, after 1930, measurements of ethnic background drop steeply, even though third-generation immigrants were often closely tied to their ethnic communities, and ethnic conflict continued to shape local politics. To avoid presenting misleading information about ethnicity, I decided to end most of my charts depicting ethnic representation at 1930.

Combining ethnic and racial data with occupational data allowed me to analyze occupational segregation by race and ethnicity. In many occupations, specific ethnic/racial groups were significantly under or overrepresented. To measure “overrepresentation,” I subtract the proportion of a specific ethnic group in the general population from their proportion in a specific occupation. For example, if Irish women were 40% of the women’s workforce but 60% of domestic workers, they would be “overrepresented” in domestic work by 20%. I calculated overrepresentation in an occupation for each decade in order to visualize change over time—for example, as the overrepresentation of Irish women in domestic service declined, the overrepresentation of African American women grew.

Importantly, overrepresentation does not indicate the proportion of the specific ethnic/racial group in a job or the population as a whole, only the difference between these two (as over or underrepresentation). This can cause some misleading visualizations of overrepresentation at times when the population of an ethnic group is very small. For instance, in 1880, Russian men were underrepresented among Boston clerical workers, but they only made up 0.2% of the Boston population overall. Even if zero Russian men were clerical workers, the lowest their “underrepresentation” could be was -0.2%. However, by 1910, Russian men were 10% of the workforce, and 2% were clerical workers. They were now underrepresented by -8%. It would appear that their representation went down between 1880 and 1910 (from -0.2% to -8%), but in fact, their presence in this occupation grew from around 0% to 2%. To avoid these counterintuitive implications, I only include data on specific ethnic groups when they made up at least 2% percent of the population.

How I use educational data

The primary education variable, available throughout this period, is “school.” In 1880, census takers asked whether an individual “attended school within the year.” This was an encompassing metric in which, for example, a student who attended only a few weeks of class could have been recorded as a “yes.” In 1900, census enumerators were instructed to record the number of months a student attended school in the previous school year. In 1910, the question was framed as “attended school since September 1st”; in 1940, since March 1st. There is evidence that families might have exaggerated their child’s school attendance, with growing enforcement of truancy laws and more cultural pressure to attend school. As such, to better measure actual school attendance in this period, I supplement census data with annual school reports produced by the Boston public schools as well as national educational statistics that encompass both public and private schools. While measures of absolute level of schooling can be estimated with these additional sources, IPUMS census data can be used to compare enrollment of different communities in Boston. With census data, the researcher can make fine-grain comparisons between attendance of different ethnic and racial groups, social classes, and genders—categories that were not often broken out separately in aggregate published reports. For example, census data reveals the high levels of school attendance among young Black Bostonians in this period, especially compared to working-class white immigrants, which is not always highlighted in the educational literature.

In 1940, a new variable was recorded by the census taker: “highest grade of school completed,” codes in IPUMS as “higrade.” This self-reported data, again, was likely overestimated, but it provides a useful estimate of the level of education for individuals with different occupational backgrounds and between different demographic groups. Also, by sorting out respondents by age, it is possible to analyze change over time simply from this one 1940 variable. For example, if we just look at the educational attainment of carpenters aged 60 and above in 1940, this gives us an approximation of the education level of carpenters at the turn of the century (when these carpenters would have been around 20 years of age). Of course, this calculation assumes a continuous occupation during the course of 40 years, and also limits our results only to those carpenters who were still alive and still working at age 60 or above, rather than all who were carpenters in 1900. However, again, as an approximation, this is an extremely valuable metric.

I use this variable in a few ways throughout the book. First, as indicated in the example above, I use it to compare the approximate education level of workers in different occupations. Comparing the educational level of workers of different ages allows me to trace the relative rising levels of educational attainment for the same occupations over time. Second, I use it to measure “assortative mating”—the percentage of individuals with a specific education level who married those with a similar education level. This is possible by using the “higrade_sp” variable (the educational level of someone’s spouse). With this variable, one can look up, for instance, the educational level of all husbands of women who are college graduates, or the education level of the wives of men who have less than an eighth grade education. In addition, similar to using age to measure changing educational levels over time, one can use the variables “higrade_mom” (educational level of an individual’s mother) and higrade_pop (educational level of an individual’s father) to estimate the respective assortative mating patterns of an earlier generation.

How I use household data

The fact that individual-level data is linked to one’s household is extremely useful for exploring household composition of different social groups and over time. One common way I used this data was to explore the class background of youth, either in school or working themselves. After coding occupations into five sectors, I created a variable to measure the sector of work of the father and mother. This allowed me to compare, for example, school attendance rates among the children of laborers compared to the children of managers and owners.

I also used household data to explore the experience of domestic workers, one of the most common occupations for women, which typically entailed living with their employers. The “relate” variable describes how someone is related to the head of household, including the category “employee.” With this information, it is possible to estimate how many employees each household had, what percentage of households employed domestic workers, as well as what percentage of domestic workers lived in their employers homes and how many lived independently.

The same “relate” variable also included a category for those who were living as boarders and lodgers. Boarders and lodgers of the same ethnic or racial background, especially among recent migrants, indicated strong networks of support among these groups which shaped many aspects of working life for Bostonians. I also estimated the number of working young people who lived in boarding and lodging houses, although I found that most young people who were working continued to live with their parents or a relative for some time.

Conclusion

Digitized census data offers some of the most valuable historical data about populations that are often marginal in the historical archive. While, between the 1980s and early 2000s, quantitative historical data was more frequently used outside the historical discipline (in fields such as demography, sociology, economics, and political science), in recent years, more historians are adopting these methods in their research. (See Steven Ruggles’ recent essay, “The Revival of Quantification: Reflections on Old New Histories” in Social Science History, 2021, on these trends). Importantly, historians are well-trained to contextualize this data itself, which is crucial for accurate historical interpretation. I hope that The Education Trap offers one model for a mixed-method approach to historical research, taking advantage of the rich sources of quantitative data now available to scholars while also critically contextualizing it as well as supplementing it with qualitative data for more comprehensive historical analysis.